Op-Ed: The Waterworks, the Worcesters, and the science we’ve been missing

December 16, 2025 | By Glenn AndersenMap courtesy of Glenn Andersen

For more than 30 years, I have lived at the southern edge of the Waterworks lands, directly across from the Worcester Range trailhead.

When I first adopted the Hunger Mountain Trail for the Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation in the mid-1990s, the entire trailhead might see three cars on a holiday weekend. Today, in peak season, we regularly see 100+ vehicles cycling through in a single Saturday or Sunday, far beyond what this narrow hillside road and fragile watershed were ever designed to accommodate.

The rapid rise of mechanized mountain bike recreation in the last 5-10 years has fundamentally altered the land. New trails have been cut, widened, or informally “improved” without full ecological review. And because the Waterworks was structured as a separate municipal entity, some users have interpreted that separation as a form of extra ownership – an unofficial permission structure to expand usage beyond what the land can sustain.

This municipal quirk has created a governance gray zone:

Town residents often assume the Waterworks is a municipal free-use zone.

The State treats adjacent Forests, Parks and Recreation land under very different conservation standards.

Meanwhile, the ecological impact does not respect political boundaries.

Trail overuse has now pushed wildlife – including black bears – out of historical habitat and into farm properties that never experienced such pressure for the first quarter century I lived here. Parking creep at the winter gate has increased trespass, vehicle clustering, and, at times, illicit activity. These are not abstractions; they are weekly realities.

This landscape is not just recreational – It is scientific archive

Beyond the immediate concerns of parking, wildlife displacement, and safety, the Waterworks and its surrounding slopes possess geological and archaeological significance that the public has not yet fully understood.

Recent peer-reviewed submissions from the HIA–Geodetic Codex project show that:

Glacial Lake Winooski once filled this valley, with its ancient shoreline running directly through the farm meadow and lower Waterworks basin.

Quartz-rich notches in the Worcester Range function as chronometer features, consistent with deglacial “melt initiation nodes” identified in the Alps, Himalayas, Patagonia, and the Baikal-Altai.

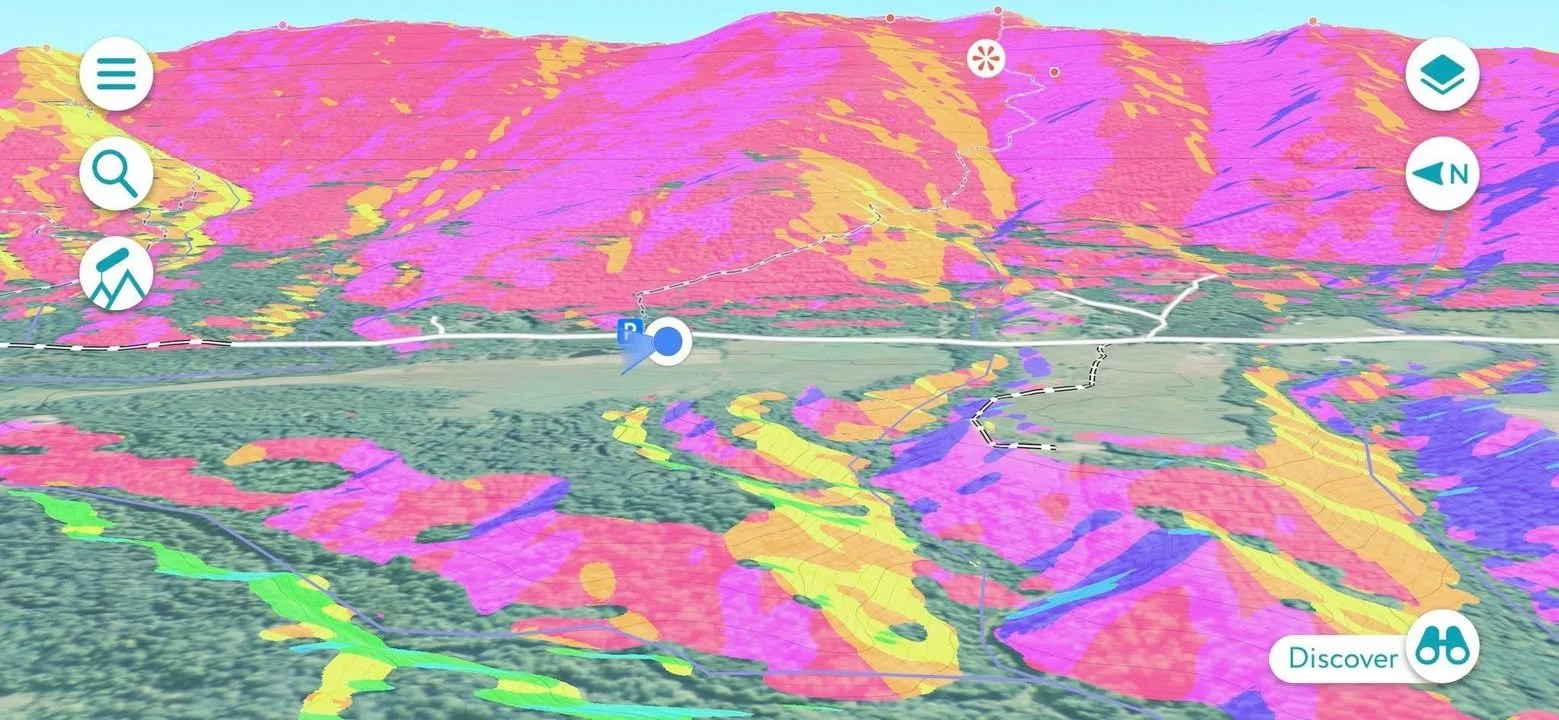

Slope-shade and LIDAR analyses reveal structured hydrological stoneworks, consistent with paleo-engineered water-management systems rather than random talus.

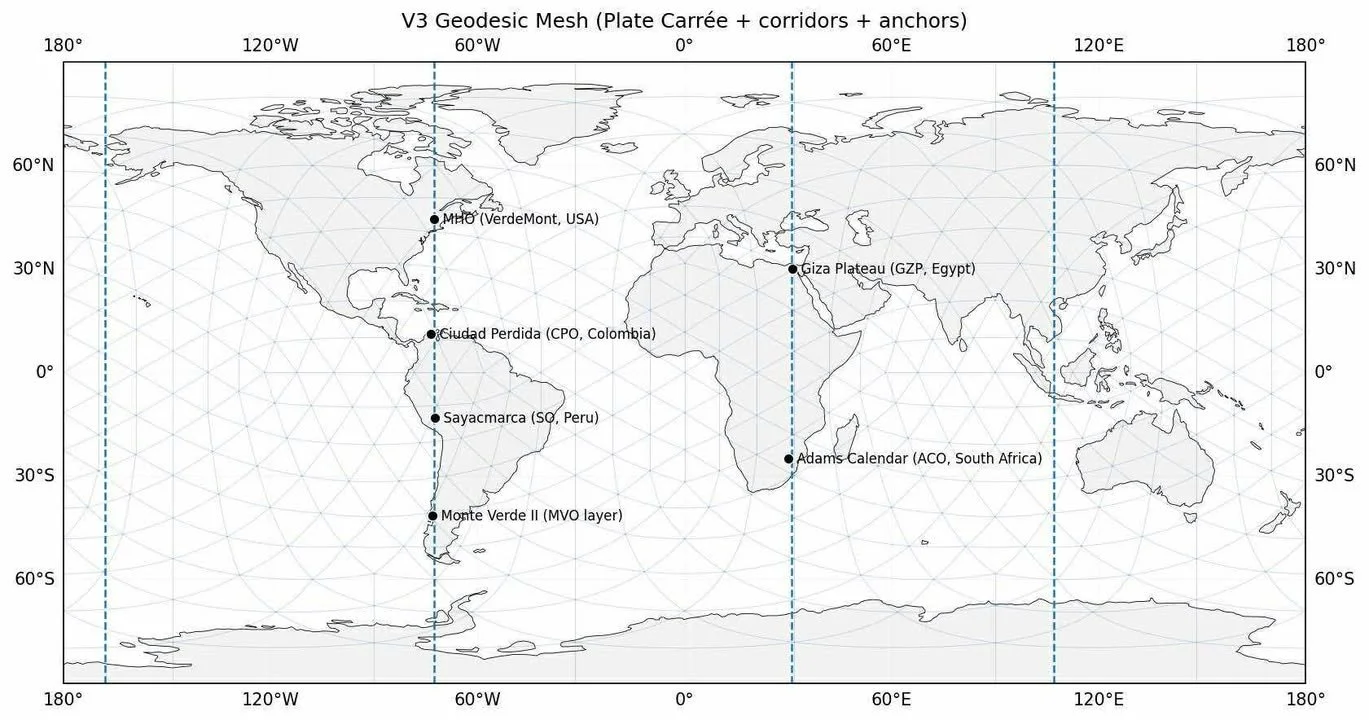

The Worcester Range is part of a long-arc, pole-to-pole geological corridor, mirrored with its twin system in Patagonia – a long, continuous north–south meridian alignment extending across both hemispheres, running from the Arctic through the Americas and onward toward Antarctica. The 72.66° West longitude passes through all of Vermont and the Worcester Range, forming part of a broader geologic corridor observable in regional landforms.

Meadow House Observatory aligns with globally recognized pre-Holocene observational sites, including Sayacmarca (Peru), Ciudad Perdida (Colombia), and Giza (Egypt).

For those who want to explore the chronometer science directly, the full PDF is available here.

Planning without this data is planning blind

Figure: Slope-Shade Geospatial Analysis of the Worcester Range, showing glacial meltwater ravines, quartz chronometer notches, and paleo-shoreline contours associated with former glacial Lake Winooski. High-contrast coloration highlights differential erosion, hydrological routing, and geomorphic sensitivity relevant to trail planning and watershed management.

The Waterworks and Worcester Range sit at the intersection of glacial shoreline geomorphology, wildlife migratory corridors, municipal land-use ambiguity, agricultural land adjacent to high-use recreation, hydrological sensitivity amplified by increased mechanized trail impact, and now an emerging body of global geoscientific evidence.

When we expand trail systems, widen corridors, or modify parking without understanding the underlying hydrology and geomorphology, we create downstream impacts – literally and figuratively.

This isn’t about stopping recreation.

This is about aligning recreation with reality.

The science now shows that:

This basin was once a glacial lake.

These ravines were engineered and reshaped by repeated meltwater pulses.

The quartz chronometer features are older and more structured than previously recognized.

The land behaves like a paleo-hydrological bowl, not a recreational blank slate.

Ignoring that is not just shortsighted – it is negligent.

Local stewardship must catch up to the facts

I support hiking, responsible biking, and the enjoyment of this land. But enjoyment must be paired with stewardship based on data, not assumptions. This begins with acknowledging that:

The Waterworks is ecologically stressed.

Mechanized trail density has exceeded the natural load capacity.

Wildlife displacement and farm incursions are measurable and documented.

Municipal separation has generated confusion about who governs what – and who protects what.

We now possess scientific evidence showing this region is far older, more structured, and more significant than previously understood.

This place is not just our backyard. It is a glacial chronicle, a hydrological archive, and a rare geological observatory still functioning in real time. Before we carve more trails, expand more parking, or widen more corridors, we must ground our decisions in the science beneath our feet.

Glenn Andersen lives in Waterbury.